Inside Out – Imaging Illness and Abjection

“I relieve myself from the normal restraint of being the ‘artist’s model’. I bring myself out of the traditional role of the passive object and place myself firmly into the role of the speaking subject”. (Heidi Yssennagger)

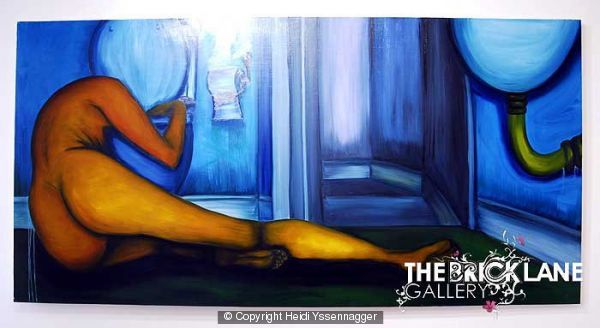

Inside Out (2008) graphically captures the “isolating space” and debility of the artist’s chronic illness whilst subverting traditional tropes of the objectified female nude. In doing so, it reclaims the body as porous and mutable, fragile and abject. In Julia Kristeva’s poetic meditation ‘Powers of Horror’ (1980), the abject is described as a pervasive human pathology which the rationalistic and coercive structures of contemporary society seek to mask and deny. Although the reality of extreme illness which Inside Out depicts is far from concealed, it images an authenticity of experience which is both visceral and grimly compelling. The genesis of Inside Out was as cumulative as it was experiential. The canvas was completed in three sittings the first of which was caught on camera and which lasted one hour; the second is described as having “filled in the space” – bringing the image “firmly into the domestic”. The third and final sitting extended to a day and projected the image back into a “phantasy setting”. Stylistically, the use of a bilious green deliberately references the colour and tone attributed to Furor Uterinus in representations of sick women, typical from the seventeenth century onwards. Describing the experience of violent vomiting, Yssennagger writes:

“A place that is not of this world; it is unreal, trippy – a carnival of queasiness that erupts in a violent volcanic expulsion of everything within – which becomes the out. One who has not been here cannot contemplate the pure torture coupled with almost orgasmic relief at cleansing the body of its putrid contents”.

Although photography has been used to ‘stage’ this work, Inside Out has been crafted using the medium of paint. As the artist notes, the genres of film, photography and performance, have since the 1960s and 1970s, remained closely associated with a critical reclaiming of the female body, and a refusal of its casual objectification. In recent decades, painting has, however, occupied something of a ‘critical limbo’, residually associated with a restrictive Modernism and its exclusion of figurative depictions of the body – female or otherwise. Discussing its neglected status, Yssennagger has nevertheless found in the medium’s opacity a meditative space for exploring contradiction and conflict:

“I find that the language of paint transcends photography. With the luminosity and sensuality of paint I am able to portray all manner of tensions – ugliness, beauty, seduction, power, vulnerability, disgust and psychological discord”.

More recently, painting has in many ways reclaimed its critical mantle. As Jon Thompson has noted, the medium no longer has “fixed conceptual concerns, or conceptual limits either”. (1) For a generation who have developed their professional practice since the late 1980s, 1990s and through into the first decade of the new millennium, it is perceived as having been freed from constraint and expectation. In self-consciously adopting the medium, Yssennagger has fashioned a powerful and resonant iconography, as fugitive of “original intentions” as it is eloquent of personal affirmation against the odds.

Dr Grant Pooke - University of Kent

1. Jon Thompson, ‘Life after death: the new face of painting’ in Ros Carter and Stephen Foster (eds), New British Painting (John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, 2004), p.1

Heidi Yssennagger and the Post-Operative Body: An Appraisal by Jon Law.

Heidi Yssennager’s art concerns itself directly with issues relating to body image, identity, and health. Her paintings present these concerns within the locus of the body, articulated through what is simultaneously the object, subject, an abject: the post-operative body. Within this space Yssennagger presents a subjective reality that uses health and illness as analytical tools in the exploration of the female form as it was formulated in classical painting. The post-operative body provides an example in which the traditional aesthetics of beauty that were imposed on the female nude are questioned and challenged. Rather than solely being a reactionary feminist critique of the classical form, Yssennagger’s art not only reminds us of our unstable relationship towards health but it is also an instance in which beauty enters a bodily state that is often deemed unworthy of representation.

In this appraisal of Yssennagger’s art I will be looking at one of her paintings as well as exploring it in relation to the relevance it has within the ongoing critiques of beauty. However, the most important contention that requires consideration is whether it is even possible to include illness and dysfunction into categories of the beautiful. Health plays an integral part within the formulation of beauty, whether it be athletic, sexual, or industrial beauty. These are merely three examples of the types of ideologies that enter into the various formulations of beauty. But it is sexual beauty that concerns Yssennagger as this is the type of beauty deployed in classical painting where the female form is saturated with its own sexuality. The dominance of the male gaze in this instance is fundamental to the ideological concept of classical female beauty.

In Frankenstein (2007) the figure with its back to the viewer is of pleasing aesthetic form; the body is composed, proportional, and balanced. She is lying on a hospital bed and red curtains line the edges of the painting suggesting that the bed is a stage. A role is being played out, as if the hospital requires a certain code of conduct. There is a parallel here between the classical nude and the infirm; they are both reduced to silence. The classical nude is represented but only as a silent object of desire, whereas the infirm on the hospital bed is not represented at all and thus also reduced to silence. However, the reflection in the mirror reveals another reality. In the mirror the reclining figure is accompanied by the luminous presence of an ileostomy bag. The painting is in fact a transcription of Velasquez’s Rockeby Venus which opens up one of the feminist aspect of Yssennagger’s art: the reclamation of the female body from the grip of traditional art forms. Here the post-operative body is explored with direct reference to the traditional aesthetic of the female nude. This re-appropriation posits itself in stark opposition to the platonic concept of beauty as well as the classical gaze that idealised the female form within a male paradigm. What appears out of this parodying of classical beauty is not just the reclamation of the female body, but also the beautification of the post-operative body.

In the mirror we see contemplation; the narcissism of Velasquez’s Venus has been replaced by the study of ones own body and its failures. In this interrogation there is a fundamentally positive movement: Yssennagger is placing herself as the passive object of the painting, assuming the posture of the silent model onto which ideals are painted, but supersedes this by simultaneously acting as the speaking subject. Mirror images are a recurring motif in Yssennagger’s art, it is about perception, how we perceive our own bodies, mediated through reflection and ideology. How we perceive an altered body image that strays from the norm. Could the only reaction be disgust and doubt? Or is there room for something more?

But viewing this scene more closely gives rise to a contentious consideration: which of the two is the speaking subject, is it the body or the ileostomy bag? If we were to remove the ileostomy bag from the painting what would be left? Besides the title which explicitly refers to monstrosity, the image is made up of aesthetically pleasing shapes and forms, the body itself is beautiful. It is the ileostomy bag which haunts this painting with its luminous presence. The eye is instantly drawn in, enticed by its very sight, it is neither overtly grotesque, nor beautiful, but once it starts to border on the neutral, a dialogue appears between the body and the ileostomy bag. The bag acts to purify and render the body operational, without it the body would fail. Out of this appears the ambiguous relationship between the figure and the ileostomy bag, there is affection, disgust, nostalgia, fortitude, and capitulation.

In this and other paintings the ileostomy bag is painted with much care and affection and leaves the viewer somewhat suspended because even through there is an abnormality in the classical view of beauty it is not necessarily shocking. There is a definitive affection attached to it, a beauty that is ambivalent. This ambivalence is maintained because the ileostomy bag is an external element, the outside threatening the inside, constantly a reminder of the failure of the body. Whilst at the same time it acts in conjunction with the body, it aids in functional processes, a site of rectification. The bag becomes the site of articulation; everything must be processed in its presence. But it must be noted clearly: the ileostomy bag does not act as a metaphor, it does not stand for anything else, it is an object that works with the body whilst maintaining an ambivalent relation to the ideological formulation of the body. It does not seek to distract from the subjects of health and beauty, instead it interrogates them.

Heidi Yssennagger’s art remains difficult presenting an extremely personal study of the body and beauty. Her nudes are exposed entities with all their troubles, doubts, pains, and accidents, but also its affection and beauty – a subjective body. It is only within this subjective reality of the body that illness can become beautiful, the illness itself can never be beautiful but it is an act of catharsis and reconciliation: exposing the beauty of the post-operative body and therefore opening up a new subjective category of beauty.

Jon Law